A Comprehensive Guide to Aperture, Shutter Speed, and ISO to improve anyone's photography

Introduction

Taking the perfect shot requires adequate skills, experience, and knowledge. Learning the terminology, tips, and tricks to call yourself a professional photographer is not enough.

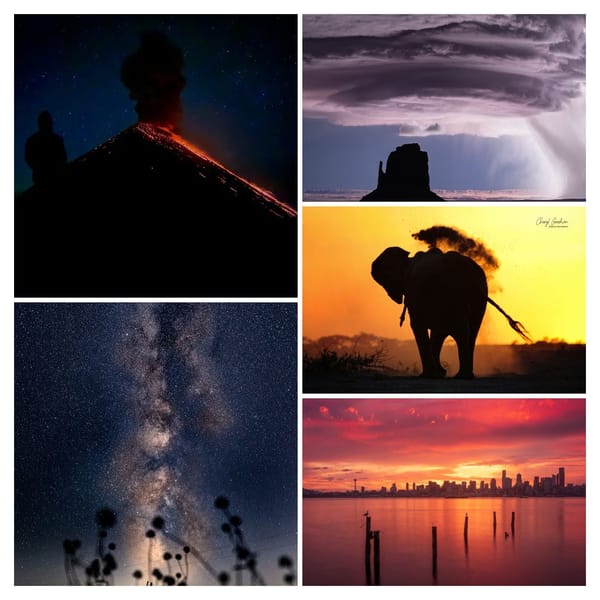

However, if you aim high in the photography world, whether as a professional looking for job opportunities or as an amateur struggling to take that wallpaper-quality landscape, you must master the basics!

This guide is necessary for all beginners, yet with detailed explanations, it can be helpful for photographers at all skill levels. Additionally, a proper reality check is always a good idea. Ensure your foundations are on point so you aren't missing anything.

While reading this guide, you might get an idea or two on configuring the settings on your next photo shoot. Make every shot count – sometimes, you don't get a second chance in landscape and weather photography.

In this article, we will cover:

- Aperture

- Shutter Speed

- ISO

And more importantly, the right combination of these three.

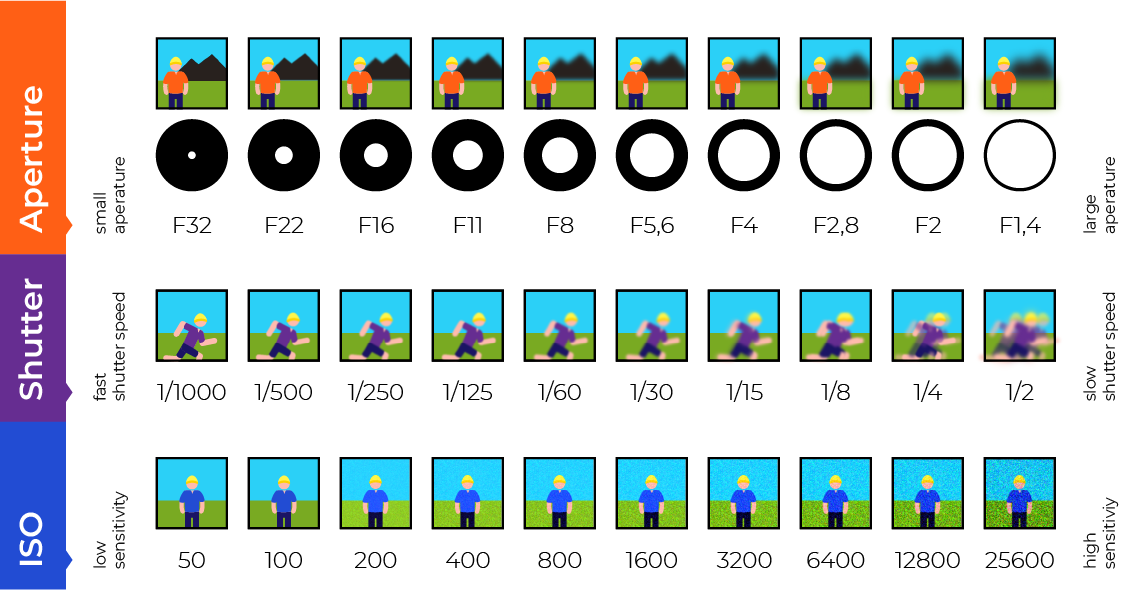

Aperture

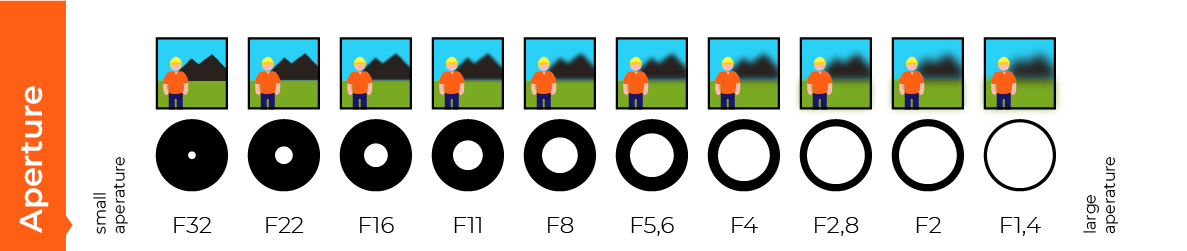

Aperture is a set of blades placed over the lens. These blades create an octagonal-shaped hole in the lens, and when they open, the light comes inside the camera, forming the image.

If the aperture opens more, more light will enter the camera. And if it opens less, less light will enter. This seems obvious for now. However, confusion might arise when we introduce the f-number, also known as the f-stop.

F-stops measure the aperture size. That is the number you see on the screen of your digital camera. If the f-number is higher, the aperture is closed more. And if the f-number is lower, the aperture is opened wider. Yes, the contrary to what would be logical.

Why is it like that?

As you probably noticed, the f-number is written as f/8, f/22, f/2, etc.

The slash, in this case, reassembles a fraction. Therefore, if you see f/2 you can consider it as one-half. An aperture of f/8 is one-eight. An aperture of f/16 is one-sixteenth. You've got the point.

Just like 1/2 cup of flour is more than 1/16 of flour. And a 1/2 pound steak is more extensive than 1/10 pound thin piece of meat.

Aperture works by the same principle. The aperture of f/2 is much bigger than an aperture of f/32. When someone tells you to use a large aperture, the f-stop is f/2, f/2.8, etc.

On most digital cameras, the f-number is between 2 and 22, although a higher range is possible. If f-number is 2, it means that the aperture is wide open. If it is 22, the aperture is almost completely closed, and minimal light enters the camera.

Here is the example of an aperture scale:

- f/1.4 (aperture almost fully opened, lots of light enter the camera)

- f/2.0 (aperture is slightly less opened, and half of the light enters compared to the previous one)

- f/2.8 (aperture is slightly less opened, and half of the light enters comparing to the previous one)

- f/4.0 (etc.)

- f/5.6

- f/8.0

- f/11.0

- f/16.0

- f/22.0

- f/32.0 (aperture is almost closed with a minimum amount of light entering the camera)

Why is the aperture important?

If you are shooting in a low-light environment (at dusk or indoors), you need a larger aperture so more light can enter the camera. If you are shooting in an environment where the light is solid (desert at noon, beach, sunny landscape), you need a small aperture. Otherwise, too much light will enter the camera, making the photo overexposed.

Aperture vs. focal length

Each lens has its focal length. The focal length is a physical attribute of a lens. It represents the distance between the lens and the point where the rays of light that have passed through that lens intersect. The lens in a camera is not a single lens but a system of many lenses. Yet, for the sake of simplicity, it is usually considered as one lens.

The f-number or aperture is not the diameter of the aperture, although, for simplicity, it is treated that way. The f-number is the quotient of the focal length of the lens (the combined focal length of all the lenses that make up "the lens") and the aperture (the diameter of the octagonal opening created by pulling the aperture toward the edges of the lens).

If the camera has a 36 mm lens (we see this on the zoom ring) and the f-number is 4 (we see it on the camera screen, f/4), the actual aperture diameter is 9 mm.

Zooming is the process where the lenses in a photographic objective move towards or away from each other. This changes the combined focal length of the lens. You may have noticed that if you set the f-number and zoom in, the camera will adjust your f-number. This is because, as we explained above, the f-number depends on the lens's focal length. When you change the lens's focal length (zoom), the f-number necessarily changes on its own.

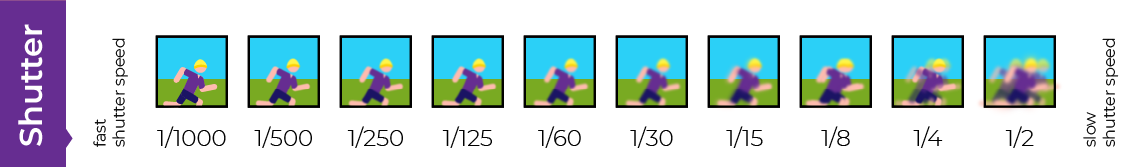

Shutter speed

The shutter is, physically speaking, the curtain that uncovers the imaging sensor, letting the light come inside the camera and form a photo.

You can compare it to a closed window that opens up when you're taking a photo. As long as the window is open, the image is being taken, and the light is projected onto the imaging sensor. If "the window" is open just for a fraction of a second, less light will enter the sensor, resulting in a darker photo. On the other hand, the image will be brighter the more prolonged the window is open.

Okay, but what does it have to do with shutter speed?

The shutter speed indicates how much time the window is open, allowing light to project onto an imaging sensor. It is measured in seconds, or to be precise, fractions of seconds.

Therefore, shutter speed can be as slow as 30 seconds or as fast as 1/100 (one-hundredth of a second), 1/1000, 1/2000, etc.

Shutter speed affects exposure in the same way as the aperture. A slower shutter speed will result in more exposed photos, and a faster shutter speed will result in less exposure, aka darker photos.

Shutter speed vs. blur

Like the aperture, which is responsible for exposure and depth of field, the shutter speed needs another factor besides the exposure.

Shutter speed controls the amount of blur in a photo. This is why you need to think of the image's subject, scene, and moving parts.

At the same time, this is a limitation and an opportunity. Why is that so?

For example, imagine you want to photograph a moving car in a low light condition. You need to set the shutter speed slower to get as much light as possible. However, you will end up with a worthless photo of a blurred car.

On the other hand, you can use this to your advantage. Slow down the shutter speed even more, and take the same photo as before. The result is a piece of art – the light trail from a car on a highway.

Although this may be a cliché, you have the idea now, so unleash your creativity.

However, you must compromise if you need to freeze that moving car in motion. Set the shutter speed fast – 1/600, 1/800, 1/1000; open the aperture, raise the ISO, and you should be on point.

Basic shutter speed adjustments

The shutter speed depends on many factors such as light, ISO, subject, and, of course, the creative goal – do you want to freeze the moment or blur the action?

We will make a list of examples to serve as a guideline. However, we strongly advise you to play as much as possible, test the limits and combinations, and try illogical things. That way, you will learn, explore, and broaden your horizons.

Subject – shutter speed

- Night landscape – 10-30" (10-30 seconds)

- Light painting – 5"

- Storm/lighting – 5"

- Fireworks – 1/2

- Landscape – 1/60

- Sports – 1/800

- Hummingbird – 1/2000

*Important – minimum shutter speed.

As a rule of thumb, if using camera handheld, the minimum shutter speed should be the reciprocal of the lens's focal length. So, if you are using a 60mm lens, minimum shutter speed is 1/60. For a 200mm lens, use a shutter speed of at least 1/200th of a second.

Use a tripod, monopod, or any stable surface or stand for a slower shutter speed.

ISO

You must have seen this a million times, even on your smartphone camera.

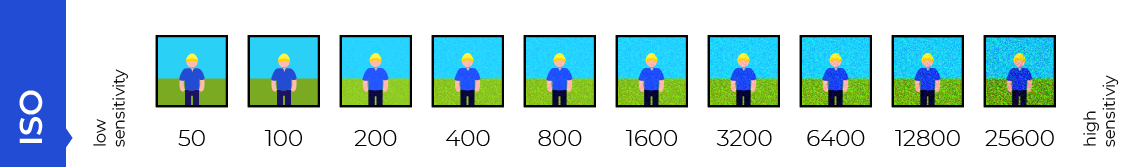

ISO value is the sensitivity of the film. Although we don't have any movie in a digital camera, the ISO value still exists and indicates the digital sensor's sensitivity. The ISO value tells how sensitive the "film" is to light.

If you are shooting in a low light environment, it is often not enough to open the aperture (to let in more light) and reduce the shutter speed (so it lets the light into the camera for as long as possible).

In that case, you are left with ISO. However, this should be your last option since ISO is a photographer's frenemy.

You may get the brighter photo, yet you will pay the price. The price is the noisier photo. Digital noise is grain on the image (tiny white/grey dots), and you've probably seen it on a phone camera while shooting in the dark.

A typical ISO scale goes from 100 to several thousand. If it is very dark, you need as much sensitivity as possible, hence a higher ISO number. However, if the ISO number is large, the photos often turn out to be noisy.

The goal is to keep the ISO as low as possible. Yet, as technology develops, with newer, high-end cameras, you can still raise the ISO without a significant loss in the overall quality.

The typical ISO value for shooting on sunny days and normal weather conditions is 100.

All that combined?

If you've read the above text carefully, you will understand that the essence of photography is how light reaches the inside of the camera.

The aperture determines how much light and focal length will enter the camera.

The shutter speed determines for how long that light will enter the camera and whether the frame is frozen.

The sensitivity of the film (ISO value) tells how sensitive the "film" (sensor) will be to the light that enters the camera.

How you adjust each parameter determines how your photo will turn out.

You may be wondering why so many parameters are needed. Isn't a low shutter speed (light enters the camera for a long time) combined with a small aperture (small amount of light) the same as a high shutter speed (light enters the camera briefly) in combination with a large aperture (a large amount of light)?

In other words, does it matter whether we expose a "film" (or its digital equivalent) to a higher amount of light for a short time or a lesser amount of light for a long time?

It does matter, and it's not the same. Different combinations of these parameters give us different features of photography, such as blurring and depth of field.

However, to understand this, you need to have a good understanding of the essence of aperture, shutter speed, and sensitivity first. When you understand these concepts, everything else follows logically.